| Well, well it was huge, the place was huge. I mean, just walking around you got lots of exercise, but when I was working in Test Block, it was in a more confined area, but we just had, everybody knew what they had to do, but yet there was a lot of camaraderie amongst the people and the people didn't...the airport hanger was across the street from us suffered mightily from the roar of the engines as they were being run. [laugh] We were pretty well, you know the sound didn't reach us that bad because they had these big concrete walls that took care of that. But yeah, you could walk around through the other parts of the base, for instance, well to go to the restroom, for instance, you had to go over to the hangar and walk through the paint part of it, which was horribly smelling. And one of the times that they brought in a B-29 before it was put into service and it was there, and even though we all worked on the base, we could only look at it from a distance, the wouldn't let us get up close. It was new, and we were all working on B-17s and then I think there were B-24s that were worked on some too. |

| How many hours did you work? |

| You'd work eight hours and you'd work for a couple weeks on the day shift and then you'd go to the swing shift and then you'd go to the midnight one. Well, I conned my way out of the midnight one 'cause I didn't want to do that midnight one, so that kinda put the kibash to that. |

| Where did you live and what did you do for recreation? |

| But my girlfriend and I actually lived on the base for part of the time we worked out there and we lived in one of the big dormitories out there. Paid about $24 or $25 a month for our room, it had two small cots init and a place to hang our clothes and a bathroom and shower down the hall, and we ate on base at the great big mess hall and it was kinda fun. [laughs] Since we, Donna and I, were living on the base, they had a recreational hall for us with a pop machines and pianos and you know, we could dance with each other and so on, and sometimes we'd get together and do things like that, or we'd go into town, and see what was going on in town. And then when we did that, we usually rode the bus, which was another speed demon at thirty-five miles an hour. You'd hear the groan of the engine as it slowly went up Sunset Hill. [laughs] And then we had to go through the gate of course, and we all had these special badges that would let us in and out, and actually, stepping even further back, before we were even allowed to work out there we had to go three days through testing. First in Spokane and then out, out on the base and were put through all this rigmarole, but once we did that, we then you had free access back and forth. |

| Work as a File Clerk |

| I don't remember that I ever had a choice to begin with, because I was stuck in a situation where I had to do the filing and nobody gave me any instructions on how to file, what to file, and what file, and so that got to be pretty boring, so then that's when I, when I found an opportunity to transfer to the Test Block. Right, and in this where I was doing the filing we always speculated that people in the, that were working there 'cause there was about eight rows of eight people each. I mean we each had our desk, and we each had a whole bunch of filing cabinets, but we often speculated as to who was really running that department because there was a great big, heavyset sergeant and then a little pipsqueak lieutenant [laugh] and nobody gave us any real direction as to what we were supposed to be doing, they'd just, ...I was the last desk in this one row and stuff would come down to me, and so I'd just file it wherever I thought would be a good place to go! [laughs] Uh, so I didn't stay there very long. |

| Work in the Test Block |

| I then went over to Test Block, and I wasn't the only Newport girl working there, Beatrice Hougen was working there too. She was working on the engines themselves, whereas putting, getting them ready to run, whereas I was working on the carburetors that would then be put on the engines, then run. And so we, and we were, it was a windowless building so we didn't have any idea what was going on outside. It was pretty quiet. And uh, she [Donna] went into office work and I went into first office work, I was a file clerk. There was something like eight people in my row, and I can't remember how many other rows there were, and I was the last one. So all of the paper shipped down first toward the one at the top line and then down at me and so that was boring as the dickens, so I transferred to Test Block. That's where they took the engines, the B-17 engines that were being rebuilt and tested them in these cells. There was eight cells in this building, and they would run them for specified length of time before they'd be shipped back to the front. And I was the one that was on my particular shift that built up the carburetors for the B-17s. Cut off the safety wires and put the fittings on so they could be run off eventually, and it was uh, and they weighed about thirty-five pounds. And the uh, and since I hadn't told my mother that, my dad was gone by this time, he was overseas, and my mother had said that she'd let me drop out of college to do this, and as long as I worked in the office. [laugh] So, before I'd go home on the weekends I'd scrub my hands good because they'd get all scratched up from the safety wires. And I never did tell her 'til the end that I was actually working in the mechanical field. |

| Impressions of Working Out at Galena |

| [It was an adventure] for somebody who had been raised in a small town it was because so many others that from Newport that worked out there too, then we'd take the bus into town sometimes and while I was out there, I still continued playing second violin in the college orchestra so that I could keep up that continuity of the college, so I hauled my violin from the base into town and then I'd go play in the concerts [laughs] and then go home on the weekends. And then also, while I was out there, we had a basketball team and we'd play, we'd do our practicing, and play at Baxter General Hospital, which is now the Veteran's Hospital, and we'd play there and the soldiers that were recuperating there would be our audience. And then sometimes we'd go over to Farragut and play, so it was...oh yeah, a lot of fun and so that kinda what went on there. |

|

The Spatsc Hellcats, 1945

Pat is 3rd from the left in the front row |

| WHAT WAS THE HARDEST THING TO GO WITHOUT DURING RATIONING? |

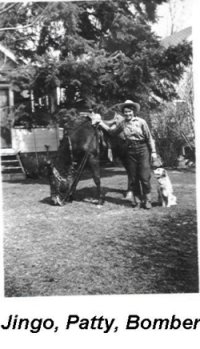

| Well first, the biggest thing for me was the rationing of shoes. Because being a horse person, I wanted to be able to buy a pair of boots, and I couldn't, because I needed that ration for regular shoes, and I conned a friend, old John Olson in Newport, he gave me one of his ration coupons so I did get my boots. But that was probably the worst and then the gas didn't really bother us that much 'cause we didn't really travel that much. Meat was a bit of a problem, but we survived and got by and yeah that was pretty much it, and the shoes because I was dying for a pair of regular cowboy boots. [laughs] |

|

| Dealing with the gas ration |

| As a way to ensure that there was enough gasoline for the military as well as those on the home front, every vehicle in the United States was issued a gasoline coupon worth a certain amount of gas per month, the most common being the 4 gallon and 3 gallon coupons. As a result of the gas ration, many turned to not using their cars, instead walking or riding the train. |

| Well, we had let's see, I think it was the "A" one [coupon] that had a little bit more, and we had that for our 1940 Chevrolet and a "B" one for the '37 Ford because we, and basically we would put the cars up during the winter time we'd store 'em in someplace. In fact the last letter I wrote uh read of my mother's she was telling about how she was going to check with Lester Banersdale, who had the Banersdale Hardware to see if he could store the '37 Ford back of that. |

| Dealing with the Stocking Ration |

| The rationing of silk, nylon, and rayon caused many women to resort to using a special type of coloring lotion on their legs and to take an eyeliner pencil to draw a seam line up the back of their legs to make it appear they were wearing stockings. This saved the wear and tear on their stockings which were extremely difficult to buy, and that were not able to be purchased using a ration stamp. |

| We painted our legs! Well you put this goop on your legs and then you had, you'd put the line in the back with a dark pencil of some kind and then of course, you know you'd go out and you'd be all set. You know you had your dress clothes on and these painted on socks. [laughs] Anytime we went to church, anytime we did anytime you went into Spokane, anytime we went to church, anytime we did anything socially, we had to do that, and on that same line, I can remember reading one of Mother's letters to Dad in '42, where she said a couple of friends of hers in Newport, this was after Dad was overseas, and she had some silk stockings and wanted her to donate them to somebody else who didn't have them and Mother refused. [laughs] They wanted her to send 'em to some of the gals who were overseas. Yeah, because that's what they, uh nurses and so on over there were desperately, you know wanted, so they wanted her to donate them. She said no [laughs] 'cause she was holding on my dad's office while he was gone, until she went to work for the Draft Board. |

| Train Wreck Beer |

| I'm sure it's in The Miner's here somewhere, but they had, the train wreck was in the Idaho section [in Oldtown]. It was on the Great Northern tracks, and I don't remember now what caused it, but one of the boxcars was filled with, with cases of beer that were going to be shipped to the South Pacific to the boys, and it burst open and so everybody was [laughing] all the townspeople and even my brother were down there with gunnysacks gathering up these bottles of beer and we always called it "Train Wreck Beer" and hid it in the basement, and so did other people. I mean everybody was getting some of it, and I was disgusted because by the time I got home from Spokane, it was gone! [laughs] But one of the boxcars was filled with whiskey, was filled with whiskey, and it didn't break open. Some of the people opened it. They popped the lock, 'cause it was sealed and started hauling out these cases of whiskey. I remember the name of one of them. I don't know if I should say the name or not, but anyway the police got involved and he, so they ended up having to return the stuff because it was obvious that the boxcar had not been busted open in the wreck.No one got into trouble if they took beer, if there, if somebody came, there was a truck and I think they, people knew who it was why they made them bring it back. But if you took away a gunnysack-full they didn't do anything. Anyway, I got to finish off what my brother brought home. |

| WHAT WAS THE PEND OREILLE VALLEY LIKE DURING THE WAR? |

| Hmmm well, number one, as far as the high school was concerned, we didn't have teachers half the time. Severe shortage of teachers and sometimes they'd just have to drag somebody in from Newport. In fact, Mrs. Schlotthauer, Dr. Schlotthauer's wife was pressed into service because they just have the teachers and the superintendent ended up being the coach, because there just weren't enough teachers. Yeah, they ended up being drafted, some of 'em, and some of 'em volunteered. Both the music teachers we had volunteered, and so it was just a case of they were snatched. It was a busy, bustling town. But so many of the young men were gone, and then a lot of the younger people left to go into the women went off to be in the service, not necessarily in the armed forces, but into other things like the Galena, so, for instance, Evelyn [Reed] she was out there, and...It didn't seem to slow the town down that much, and especially when all of the men that were left here had access to Farragut when they were building it we also had, I think I mentioned before that we had sailors that would come visit us. |

| What was your best moment? |

| Gosh, my best moment, oh hmm, probably the day that I met my dad when he came in on the train at the GN [Great Northern] depot in Spokane on his return from the, from overseas, for the first time, when he first got back, it was so exciting to see him standin' there in his uniform and it was just really exciting. Well and before that, one of the things that I had done, my dad had sent me some of the ribbons that the servicemen got and I had a letter jacket, a Letter N jacket, and I pinned them on that Letter N jacket and this was before this, and I was standing in the, waiting for the bus to come in the bus depot in Spokane, and the MP [military police] guy came up and said, "You're not entitled to wear those, please take them off." [laughs] So I had to take those off and stuck 'em back. [laughs] But anyway, yeah when I got to see my dad was the most... |

| What were the end of the war celebrations like? |

| I'm pretty sure I was still out at Galena at that time, so it was a big celebration of everybody over there. But with that somebody evidently heard it on the, some way or another and somebody started tootin' the horn and everybody else tooted the horn and so we all got all excited and were glad to see that it was the end, I mean it was really, really a relief. |

| Like many young women, Pat had to return to the life she had before going to work at Galena. This included going back to college, because now that her dad was home she was back to toeing the mark again, however, many remember it as an exciting time, a time where they had more freedom than ever before. |

| WHAT DO YOU REMEMBER MOST ABOUT THE WAR YEARS? |

| Oh yeah, I thought it was an exciting time. Number one because I had so much more freedom. My mother relied on me for so many things here at home and also up at Bead Lake, but also I was able to make the decision to leave college and go to work without having a hassle, so it was a case of, seemed to be more freedom to make choices and I hoped I made good choices. And yeah, everybody was, I don't think they felt depressed or anything because there was so much going on. Everybody was listening to the radio, watching the newspaper, so that you could follow what was going on overseas. That to me was like I say was more a freedom that I had never experienced before, because my dad was quite a strict taskmaster, and so all of a sudden I was given responsibility. Oh, the camaraderie. You know we all felt somehow connected. It was uh, and maybe because that was the age we were too, but yeah, everybody was, it was an exciting time. |

|

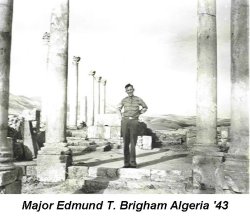

| The Family Picture Major Brigham Carried Through the War |