Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, all industries in the United States were refitted for war production. Automobile manufacturers changed from making cars to tanks and jeeps, manufacturers of washing machines and other peacetime items also went to producing rifles and other things for war. Then anyone of working age was asked to go to work in these industries now designated as essential to the war effort.

All non ferrous metal mining, milling, smelting, and refining and all logging and lumbering industries in the area were designated as essential war production activities. (Newport Miner, 10 September 1942, pg. 1)

The push following the industry refitting, was to get as many workers as possible, calling for people to come and work for the war effort. Because of this patriotic call, men and now women that worked for these essential industries were frozen to their jobs for the duration of the war, a move that meant employers could not hire workers away from essential industries, and that made it very difficult to change jobs. On some occasions, the worker could obtain special permission from the U.S. Employment Service to change jobs, but the worker had to be hired by another essential industry. In most cases, men that were of draft age were given a chance to either be drafted or work in a factory, and in all cases this choice was given to consciencious objectors. Governmental controls over the disposition of manpower was finally lifted at the end of August 1943 allowing workers to finally be able to change jobs without special permission.

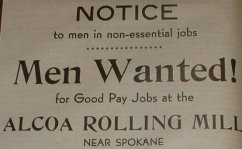

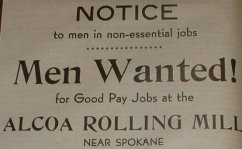

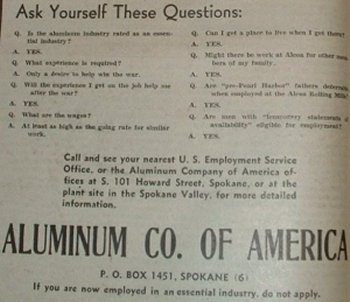

The Newport Miner, Spokesman Review, and Spokane Chronicle, all of which served the entire Pend Oreille Valley were full of advertisements for workers for war production industries throughout the state, whether those workers were men or women, as shown in the advertisements (courtesy Pend Oreille County Historical Society) from the Newport Miner below.

|  |

As you can see in the Alcoa advertisement above, workers that were already working in an essential industry were asked to not apply, as the goal was to fill up the war industry with people that were unemployed or employed in non-essential work. Women of a certain age were also called upon to do their patriotic duty, and free up men for the fighting. This proved to be the case throughout the war, with an increasing number of women entering the previously male-dominated workforce. These "Rosie the Rivetors" could now be found welding, pipefitting, riveting, and doing other work which until the war was seen as occupations reserved for men. The men that they replaced were freed up to join the military, which many did upon reassurances that when they returned their positions would be there for them, if they wanted.

Men and women flocked to the Kaiser shipyards of Portland, the aircraft factories in Seattle and Spokane (Boeing Field and Galena, respectively), and other places around the country. Galena (now Fairchild Air Force Base) just outside of Spokane saw many young women and men from the Pend Oreille Valley working there, as did Farragut Naval Training Station in Athol, Idaho especially when the training station was being built.

There was a great need for lumber during the war, for military housing, shipbuilding (PT Boats were wooden hulled, and the decks of most of the fleet were wooden), and for the containers needed to ship military supplies overseas. Because of this great demand, all civilian building was eliminated for the duration of the war, thereby insuring that there would be enough lumber to satisfy the needs of the military. The Pend Oreille Valley, being a heavily wooded area was one of the places that the military received its lumber.

The Cusick and Newport Diamond Match mills provided a great deal of lumber for the war effort. There were many residents of the Pend Oreille Valley that worked in the mills, all of which were frozen on their jobs as soon as the war started, and the only way to leave the mill was to volunteer for military service, or as previously stated, appeal to the U.S. Employment Service, as other industries could not hire them away from the job they were in.

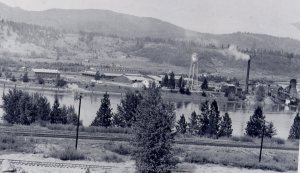

|

| Diamond Match Mill, Newport courtesy Pend Oreille County Historical Society |

Bob Rednour There was a great need for lumber especially for military housing during the war. A great deal of lumber produced here at the Diamond Match mills in Newport and Cusick went into building the Naval Training Station at Farragut, which took five years. While those working in the mills were frozen to their jobs, men over the age of 18 had to still register with the War Department. For replacements the mills didn't even have to advertise, there was a standing list of people that wanted in, this made it possible for Diamond Match to be pretty selective on who they took to work for them. In fact, timer thrived for years after the war, because of the post-war Suburbia boom.

Bill Piper But I do know that through the war, old Carol Graham had an old RD6 they called 'em. It was one of the first diesel bulldozers they put out. That thing kept breaking down all the time and about the second year of the war the Diamond Match bought him a brand new TD10 which was something. But of course everything was going strong. The camps and everybody had money. The Diamond had camps on Priest Lake, they had floating camps, which had barges and tugboats that towed equipment around, they had a camp on Middle Creek here in Pend Oreille County and there were pole camps too.

Faith McClenny Well, for my father's sawmill business it was good because the large sawmills had the big military orders, for the camps, and this type of thing and for the local people or even builders in Spokane, he had a lot of business, and was kept busy all the time.

One of the other important industries in the Pend Oreille Valley was the mining of non-ferrous metals in the northern reaches of the Valley. In the mines around Ione, Metaline, and Metaline Falls zinc and lead were taken out of the hillsides. Zinc was especially important to the war effort, as from it cartridge brass, electric batteries for planes, trucks, jeeps, tanks, and self-propelled artillery, pigment for paint, and chemical warfare zinc for smoke screen materials were produced.

| Aerial View of the Metaline Falls Lead and Zinc Mine courtesy Pend Oreille County Historical Society |

Bob Rednour The mines were going full blast, producing the lead and zinc ore for the war effort. They too had to keep places for the servicemen just like the mills did.

Bob Beaubier Well they were mining for lead and zinc and uh our job was to mine the ore to go to the concentrator and the concentrates were then shipped off and refined to smelter, but that was not done with the mine until it was shipped away someplace.

However, there seemed to be a continuous lack of manpower for the mines, as evidenced by various articles in the Newport Miner blaming the lack of manpower on not enough food for the workers thanks to OPA (Office of Price Administration) rationing restrictions.

| The Metaline Falls Lead and Zinc Mine courtesy Pend Oreille County Historical Society |

While the lumber and mining industries were important to the Pend Oreille Valley, there were a few other industries considered essential to the war effort here in the Valley. Chief among these was agriculture. As the Pend Oreille Valley was and still is a rural area, many of its residents were involved in some sort of agricultural occupation. Beef, dairy, sheep, grains and others, all of which on a small scale could be found here, and all products were reserved for the war effort. All livestock was required to be sold at the livestock yard in Spokane to be purchased by the government to feed the military, only a small portion was allocated to consumers, and was of course rationed.

Bob Rednour The beef we raised was designated for the military. Everything taken to Stockland (the stock yards) had to be reported to the government so we couldn't really just sell meat to anyone.

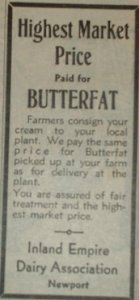

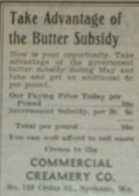

Milk and cream from the local dairies and each individual farm was collected and sent to the Newport Creamery or into Spokane to the Spokane creamery. Housewives would collect their cream and send it to various collection locations around the county and town of Newport, whereupon they would receive money for the cream sent in. With this money, housewives would estimate what they could purchase at the store to go with their ration points, due to the Pend Oreille Valley still not out of the throes of the Depression.

courtesy Pend Oreille County Historical Society

Norma Rednour My mother used to take the money that she got from turning in her cream, and then make her shopping list according to what she had received.

Bob and Norma Rednour The creamery in Newport was where the Eagles building is now, there on Union, but there was a collection place behind what was the Ford garage until last year, and one down by where the Food Fresh grocery store is. Many places between Cusick and Spokane along the railroad tracks there were cream stops. The milk train used to stop on its way into Spokane and pick up the milk and cream that farmers put out to be taken into town. The creamery in Spokane would then send the cans and your money back out on the train. This was also the train that most of us took when we rode the train to Spokane but it was a pain to take because it stopped all the time.

While the Pend Oreille Valley had its own essential industries, the areas around the Valley held opportunities for its residents to work for the war effort. Places like the Spokane Air Depot, more commonly known as Galena, where they repaired B-17 and B-24 engines, and Farragut Naval Training Station, while it was being built saw many Pend Oreille Valley residents (especially the young people) working there.

Pat Geaudreau I left college in Spokane initially to go and work as a secretary out at Galena, that was the only way my mother would allow me to go help in the war effort, as a secretary. There was 8 rows of 8 people in this room doing filing, each of us with our own desks and file cabinets, and I was in the last row. No one told us how to file, or what to file where, so I came up with my own system, I don't know whether it was right or not, but as the papers made their way down to me I would file them where I thought they belonged. I got bored of filing, so when there was a chance to go and work in the test block, I jumped at the chance. I went to work on the testing block, putting carburetors back together for B-17s at 35 to 50 cents an hour for an 8 hour shift. Other places were working on the whole engine, and when all the pieces were put back together, the engine would be tested for 3 days and then sent overseas.

Evelyn Reed I was a typist that was, that was almost unusual, everybody wanted to be riveting and doing all of these, making more money and things, and because I had just finished all of these typing classes and so on, they gave me a typing test. And so I went in and the first job was so boring that I just wanted to quit and so they gave me a different job, and it was really quite, quite a neat job for a seventeen year old. I worked in the Tool Crib. Each of the four large hangars had a center deal that was called the Tool Crib, and it was upstairs and they checked their tools in and out, and I signed clearances for people that were returning things or whatever, and I did filing and some typing so I did a type of office work most of the time I was there.

Norma Rednour I worked for the Interstate Telephone Company from 1942 to 1944, on the switchboard at 19 1/2 cents per hour. I worked in Newport, out at Farragut when it was being built, and at the Postal Telegraph office in the Davenport Hotel until I got married. Because this was such an essential part of the war effort, I was frozen to my job, and couldn't even get a release from the telephone company to go to work for Mountain States Electric Company. When I was at the Farragut "Office" (the switchboard was inside a small house), the base was growing so fast and they were adding so many lines, we had to re-learn the circuts every day because they changed daily. I met a lot of different people when I worked for the telephone and telegraph company, and getting to meet the different soldiers and sailors while at the Davenport was exciting.

As the people of the nation and the Pend Oreille Valley were going to work in unprecendented numbers, they were also being having to face the hardships and inconveniences of the rationing system that made many everyday items not only hard to get but in some cases totally unavailable. Go to the rationing page to read more.

| Copyright © 2004 by Kristen Cornelis |